Socio-political context & implications for teaching/educational policy

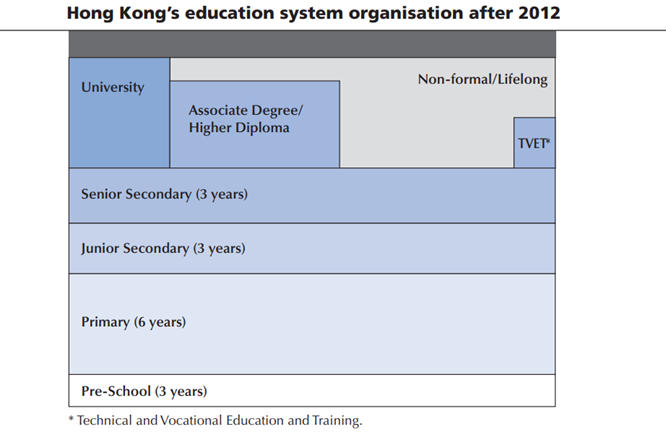

Although Hong Kong is a part of China, the education in Hong Kong is based on the education of the United Kingdom, particularly the English system. Prior to the implementation of the new education system in the 2009–2010 academic year, the Hong Kong education system followed the typical British system (6-5-2-3 structure). The current educational system is organized in a 6-3-3-4 pattern, which means six years in primary school, three years in junior (lower) secondary school, three years in senior (upper) secondary school, and four years in university and this pattern is consistent with the one in mainland of China. The Education Bureau (EDB) is responsible for the education system. Government has very minimal intervention in education. Unlike other cities in China, the government doesn’t rank HK schools. Most schools in HK are public schools, which are regulated by government, while private schools have complete autonomy over their curriculum, teaching methods, fees, and admission procedures. They are not required to follow the Hong Kong Education Department’s recommendations. The HK education adopts a multilingual approach in instruction: Chinese (Cantonese), Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua), and English in primary and secondary education; Chinese (Cantonese) and English in higher education.

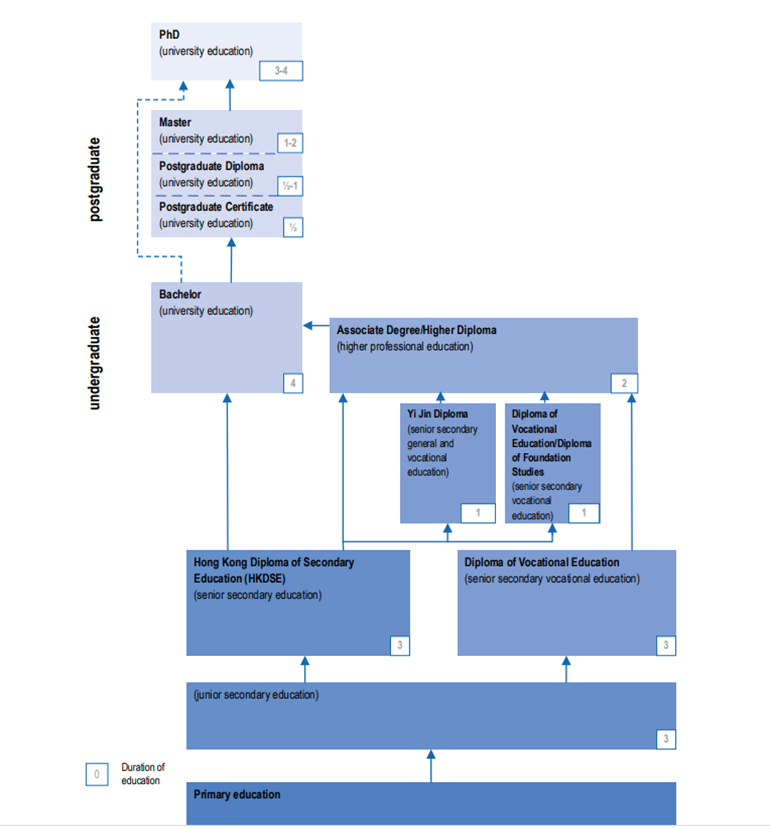

Students attend public schools (6 to 18) for free. It is compulsory for children to attend primary and junior secondary schools between ages 6 to 15. HK also host international schools with their own admission requirements. As in other parts of the world, the so-called elite schools in Hong Kong are concentrated in several “good” and expensive districts, so admission to these schools is initially contingent on whether one’s family can afford to relocate to those districts. Students need to take HKDSE exam (Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education) to enter higher education since 2019. Higher education in HK is divided into 2 levels: Sub Degree Level:2 years and professionally-oriented;

Degree Level:include bachelor, master and doctor (PhD). (Nuffic, 2018).

Source: OECD (2010)

Source: Nuffic (2018)

Current trends in educational policy and practice (e.g. relevant curricular reform cycles) & regional differences

In Hong Kong, there has been a call for a change in the local aims of education to meet the global needs of the 21st century (Education Commission, 2000). The specific proposed measures of the education reforms aimed at student-focused teaching, broadened learning experiences and opportunities to pave way for lifelong learning, catering for the diverse needs of students, and improving the assessment mechanism to supplement learning and teaching. These proposed aims and measures, if successful, were expected to change teaching and learning fundamentally. However, despite such an educational, social, and economic context that calls for innovation and an improved performance in the 2009 PISA results (OECD, 2010), international comparison indicated that the pedagogy of Hong Kong teachers was not particularly innovative at the classroom level (OECD, 2014). These results justified the Education Bureau’s (EDB) to put forward a key strategy to enhance teacher capacity and quality education through professionalization and continuous professional teacher development (Ko, Cheng & Lee, 2016). However, this effort costs time and money and inevitably increases teacher pressure and workload. The EDB has been criticized for implementing too many top-down education reforms without sufficient negotiations and communications with the practitioners (Cheng, 2009; Cheng & Walker, 2008). Disillusioned local teachers described the pressure to compete is strengthened instead of weakened (Choi & Tang, 2009). Apart from the pressures of education reforms and professionalization, the school place allocation system, streaming and setting, medium of instruction policy, and examination-oriented culture are regarded as the major system-wide structural challenges affecting teacher and school effectiveness in Hong Kong (Ko, 2010). Various models of teacher effectiveness (e.g., Campbell, Kyriakides, Muijs & Robinson, 2003; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008; Marzano, 2003) indicate that consistency and variation in teaching practices may affect individual teacher effectiveness and collective teacher effectiveness, but have not received enough attention thus far in practice.

In China, waves of curriculum reform for quality-orientated education since 1999 (Dello-Iacovo, 2009) indicate a strategy to enhance education quality through strengthening curriculum management and teaching practices (Marton, 2006; Wong, 2008). Eager to shift from a traditional teacher-centered pedagogy, Chinese educators have imported approaches of Western pedagogy, such as inquiry-based learning, collaborative learning and other methods that emphasise greater student-teacher interaction (Dai, Gerbino, & Dailey, 2011). These changes have led to discussions and trials of student-centred instruction at the central government and school levels to promote teacher effectiveness in classroom (Guan & Meng, 2007). Professional development of teachers is clearly wanting, as teachers are the main agents of instructional change (Paine, 1997; Wang, 2011; Wang & Li, 2010). At the school level, teachers are used to work collaboratively in collective lesson preparation, classroom observation and mentorship programmes ever since the system of teaching and research was built in 1950s (Hu, 2005). With increased demand for teaching effectiveness, strategies to promote pedagogical practices have focused on more collaborative work that can help teachers to develop innovative instruction methods (Wong, 2012). Teachers have gradually employed and used appropriate methods of evaluation and assessment to keep records of classroom interaction and improve their methodological competencies, such as problem-solving methods and individual teaching methods.

Current international examinations (PISA, TIMSS)

Compared to other participating countries in PISA, Hong Kong (China)’s performance in international examinations has been consistently high, particularly in mathematics and reading. However, a longitudinal comparison reveals a downward trend in Hong Kong (China)’s performance.

Hong Kong(China) has been participating in PISA+ since 2002, the first Chinese region to do so, and the results were outstanding – Hong Kong(China) ranked first in mathematics (M = 560), third in science (M = 541) and sixth in reading (M = 525) out of 43 countries and territories (HKCISA , 2003) . However, in 2018, 15-year-olds in Hong Kong (China) score 551 points in mathematics, 517 points in science , 524 points in reading literacy. Compared to the OECD average score (M mathematics = 489; M science = 490; M reading=487), maths and reading both ranked fourth out of 77 participants, while science ranked 31st out of 34 participants. The study showed that Hong Kong (China)’s science average was one of the largest declines in performance (OECD,2018). It is also worth noting that there are significant gender differences. Girls performed significantly better than boys in all three dimensions of reading (35 points higher), mathematics (6 points higher) and science (9 points higher). Nevertheless, the differences in reading achievement (5.1 %) due to the economic, social and cultural circumstances of students and schools (ESCS) were among the smallest in all participating countries and regions, as well as the percentage (12.7 %) of immigrant students with low reading achievement (below proficiency level 2) (OECD,2018).

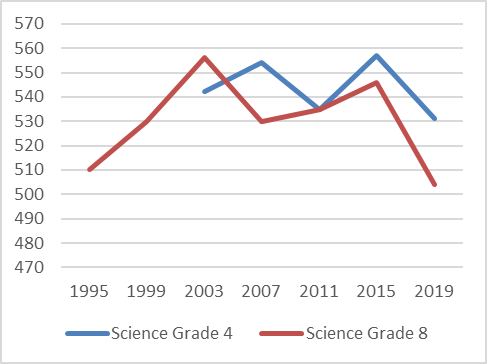

Hong Kong (China) continues to perform well in mathematics in another international examination TIMSS 2019. In mathematics at both 4th grade (M = 602) and 8th grade (M = 578), Hong Kong SAR was the top performers, as well as other East Asian countries—Singapore (M 4th grade= 625; M 8th grade = 616), Chinese Taipei (M 4th grade= 599; M 8th grade = 612), Korea (M 4th grade= 600; M 8th grade = 607), and Japan (M 4th grade= 593; M 8th grade = 594). However, the performance in the subject of science at both grades, which is in line with the above-mentioned PISA results, has prompted the education system to reflect in Hong Kong. In science, the mean scores for Year 4 and Year 8 are 531 (ranking 15/58) and 504 (ranking 17/39) respectively (TIMSS, 2019), which compares very favorably with other East Asian countries. Since participating in 1995, there has been an occasional improvement but a general downward trend.

Source: IEA’s Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study TIMSS 2019 http://timss2019.org/download

Source: IEA’s Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study TIMSS 2019 http://timss2019.org/download