Socio-political context & implications for teaching/educational policy

In the United Kingdom, education policy is specified for four different countries (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales). The governance systems of each country differ from one another, but some features are similar. Policies are generally outlined within each of the four countries and aim to give schools and teachers a more prominent role. We mainly focus on England for context information for this report.

ENGLAND

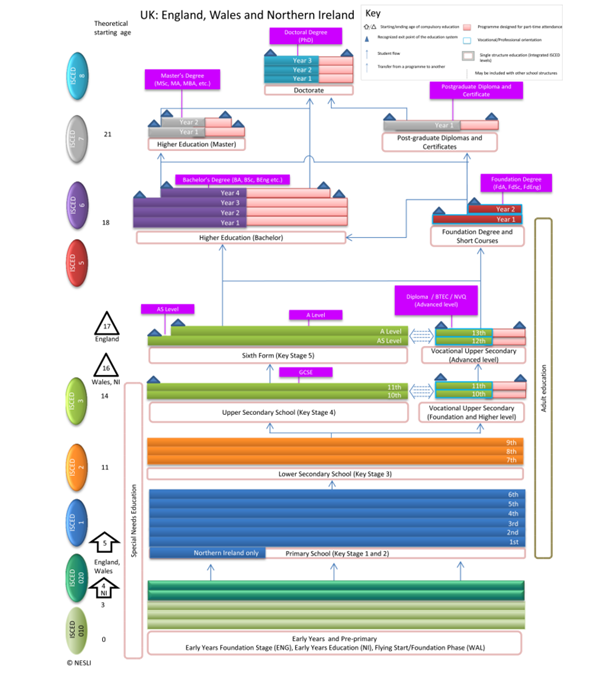

In each country there are five stages of education: early years, primary, secondary, further education and higher education. For Early Years Education, the government publishes the policy, all 3-4 year-olds continue to be entitled to 15 hours of free early childhood education which has been extended to disadvantaged 2-year-olds. Meanwhile, compulsory education covers from age 5 to17 (extended to 18 for those born on or after 1 September 1997), including primary education (key stage1-2) and secondary education (key stage3-5). Further Education is non-compulsory, and covers non-advanced education which can be taken at further education colleges (including tertiary) and Higher Education institutions (HEIs).

The ‘basic’ school curriculum consists of the national curriculum, religious classes, and sexual education. Unlike public schools, academies and private schools aren’t required to follow a national curriculum (GOV.UK, 2014). The new national curriculum framework was published in September 2013, and implemented from September 2014. Likewise, in vocational education and training, England has set forth a new national strategy, Rigour and Responsiveness in Skills (2013), to support the vocational education and adult training system, which is a broad and complex qualifications’ system.

Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education, Children Services and Skills) conducts school evaluations. There are two government departments in charge of the education system: the Department for Education, which sets education standards and regulations, and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, which runs tertiary education. School funding is public for local authority schools; free schools and academies are not part of the local authority but have greater autonomy in areas such as staffing and curriculum (Geva et al., 2015).

See figure 1 for a graphic representations of the educational setting of England, Wales and Norther Ireland.

Current trends in educational policy and practice (e.g. relevant curricular reform cycles) & regional differences

ENGLAND

The Outcome Delivery Plan(2021 to 2022, published by the Department for Education on 15 July 2021, replaces the Single departmental plan as the guiding policy for education reform in England. The current policy focuses on build back better after coronavirus, rather than the previous one’s emphasis on providing world-class education and training for all whatever their background. The plan sets out four priority outcomes, which are boosting economic growth, raising educational standards, supporting vulnerable groups through high quality local services, and providing high quality early education and childcare. The main strategies are as follows:

- Enhancing technical and higher technical education to meet the needs of the job market, driving the growth of apprenticeships and giving adults and young people ample opportunities for re-education and retraining.

- Providing funding and support for schools to improve the quality of teaching and leadership in all areas. Support children to catch up on the learning lost through COVID-19 disruptions.

- Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of local public services for children and young people, addressing the barriers that prevent vulnerable and disadvantaged children and young people, increasing participation and involvement in education and training, and creating safe and loving homes.

- Maintaining an adequate supply of local childcare markets and increasing the proportion of children who reach the expected level in all areas by the age of 5 so that every child can succeed (GOV.UK, 2021).

Current international examinations (PISA, TIMSS)

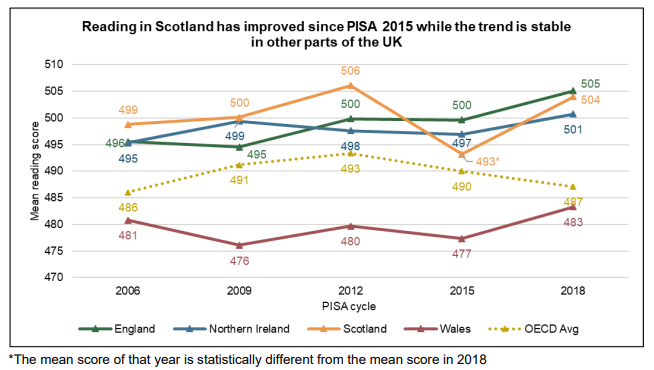

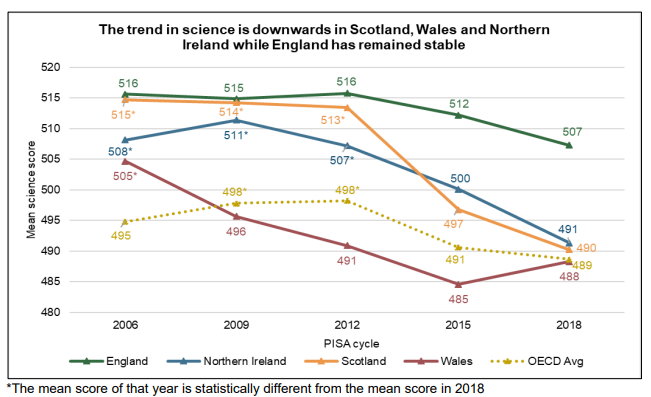

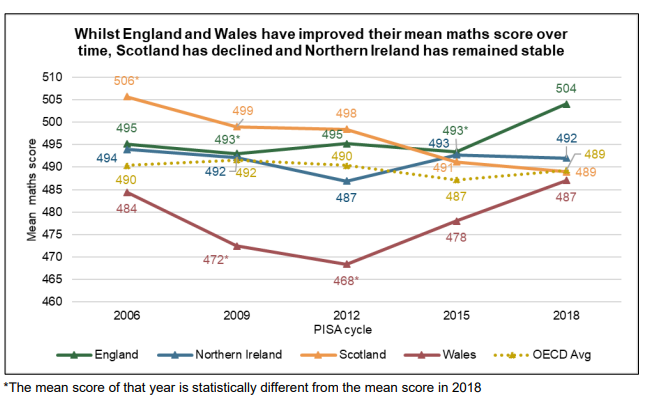

Based on current results of popular international testing studies such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2018) developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], across England (M = 505), Northern Ireland (M = 501), and Scotland (M = 504), there were no significant differences in reading scores, and all were significantly above the OECD average (M = 487). There was a significant difference in Wales’ (M = 483), mean reading score from the other countries of the UK, but there was no significant difference from the OECD’s average. England’s mean scores in science (M = 507) and mathematics (M = 504) were significantly higher than those in other parts of the United Kingdom, as well as higher than the average for the OECD(M mathematics = 489; M science = 489). In Scotland(M mathematics = 489; M science = 490), Wales(M mathematics = 487; M science = 488), and Northern Ireland(M mathematics = 492; M science = 491), as well as in the OECD’s average, no statistically significant differences were observed. The attainment gap between high and low achievers was largest in England (262 score points) and lowest in Scotland (244 score points). Wales (250) and Northern Ireland (255) lie between the other 2 UK countries.

In reading, PISA scores have remained stable over time, with the only statistically significant change being an increase in reading scores in Scotland (compared with 2015), following a similarly sized decline in 2015 (Department for Education, 2019).

Source: PISA 2018 database; Bradshaw et al., 2007; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Wheater et al., 2014; Jerrim et al., 2016

As for science, in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the mean scores in 2018 were significantly lower than in 2006. That explains the large gap between England and the rest of the UK. In Scotland, where science scores in earlier PISA cycles were close to those in England, the downward trend has been pronounced (Department for Education, 2019).

Source: PISA 2018 database; Bradshaw et al., 2007; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Wheater et al., 2014; Jerrim et al., 2016

In mathematics, there is a more mixed picture. Since PISA 2006, when Scotland outperformed the rest of the UK, Scotland has shown a decline that is not as pronounced as that in science. Welsh math scores have improved after declining in earlier cycles of PISA, while scores in Northern Ireland have remained largely unchanged. England, on the other hand, improved markedly in mathematics in PISA 2018, after successive cycles with stable scores (Department for Education, 2019).

Source: PISA 2018 database; Bradshaw et al., 2007; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Wheater et al., 2014; Jerrim et al., 2016

The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is a four-yearly cycle survey of the educational achievement of pupils in years 5 and 9 developed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). In England, pupils’ average performance significantly above the TIMSS CenterPoint (500) in mathematics and science in both years 5 and 9 in 2019 TIMSS. Compared to 2015, England’s performance significantly improved in mathematics at year 5 (M = 556), decreased significantly in science at year 9(M = 517), and remained stable in mathematics at year 9(M = 515) and science at year 5(M = 537) (Richardson et al., 2020).

In Northern Ireland, mathematics (M = 566) and science (M = 518) attainment for 9 -10 year old students (Northern Ireland participated only at the younger age range) in 2019 TIMSS remains high, which were not significantly different from scores in 2015(M mathematics = 570; M science = 520) or 2011(M mathematics = 562; M science = 517). In mathematics, it ranks sixth out of 58 participating countries, but performance in science remains significantly weaker, although significantly above the international average. Scotland and Wales did not participate in the 2019 TIMSS test.