The Dutch education system combines a centralized framework and policies with decentralized administration and school management. This framework provides standards with broad achievement goals and supervision set by central government, while schools and institutions have a great degree of educational and administrative autonomy on matters related to resource allocation, curriculum and assessment. Therefore, one of the key features of the Dutch education system is freedom of education. In the Netherlands, it is compulsory for all young people aged 5 to 16 to attend school full-time or until they have obtained a basic qualification. The Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science works with local governments to coordinate educational policy.

Division characterizes education in the Netherlands. It is tailored to the student’s specific requirements and background. There is a key moment at the end of primary education when pupils decide the type of secondary education they want. The overall principle is to enhance equity and quality.

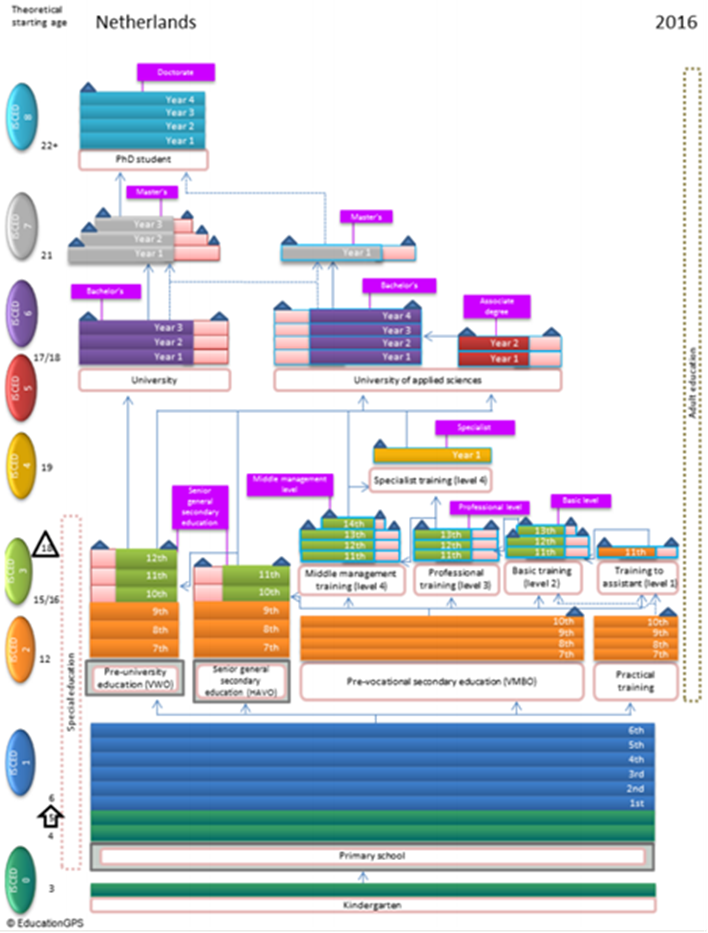

The education system is divided over schools for different age groups: Primary education (4-12yrs), Secondary education (12-16/18yrs) and Tertiary education (16yrs and older). Schools are furthermore divided in public, private (religious), and general-special (neutral) schools. The Dutch grading scale runs from 1 (very poor) to 10 (outstanding). In primary and secondary education, the students in some schools are taught in Dutch and English.

Primary education

Children attend elementary school (from group1-group8). In group 8, pupils complete the Cito Eindtoets Basisonderwijs (Cito test; which not compulsory but is widely applied). The test results help the teacher’s to recommend the best suited type of secondary school. The opinion of the pupil and his/her parents are also weighed in the decision.

Secondary education: early differentiation

Dutch high schools are divided into three streams: one to prepare students for vocational training (VMBO), another to prepare students for university (VWO), and a middle stream to prepare students to study at universities of applied sciences (HAVO).

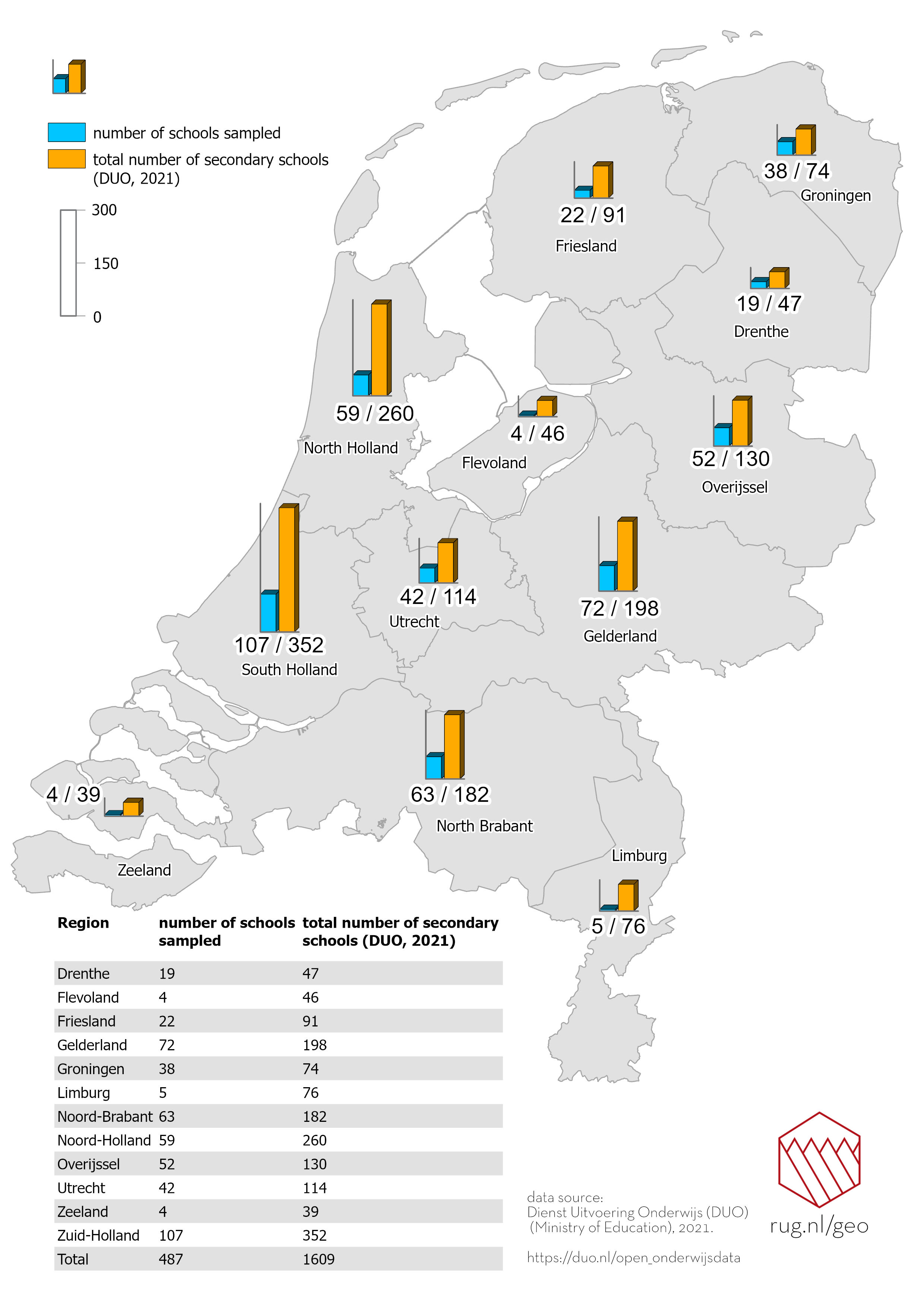

For a graphic representation of the Dutch educational setting see below.

Source: OECD (2016)

Gradual shift to higher tracks

Between 1990 and 2011, the proportion of students in pre-vocational education (VMBO) decreased from 58% to 39%. General secondary education (HAVO) and pre-university education (VWO) rose from 32% to 44% (MoECS, 2012).

Level of (school) autonomy

The Netherlands has a highly decentralised school system (86% of decisions are made by school, OECD average is 41%). There is no national curriculum (even though there are national end examinations). School autonomy is grounded in the principle of “freedom of education”, guaranteed by the Dutch Constitution since 1917. Parents are free choose the schools for their children.

Responsibilities

Schools have equivalent public funding. Approximately one third of the pupils in primary education attend denomination free schools, one third attend Catholic schools, and one quarter attend Protestant schools, and the remaining schools attend in other types of government-dependent schools. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (MoECS) has overall responsibility. There is a large intermediary structure of school support organizations.

Expenditure

The Netherlands achieves good results with an average level of expenditure. 3.8% of GDP is sent on primary and secondary education, similar to the OECD average. Education expenditure has increased (2000-2012): 0.6% (OECD average increase of 0.2%). School funding mainly reflects the number of students (extra funding is provided for students with extra needs). School boards receive block grants for staffing and operating costs.

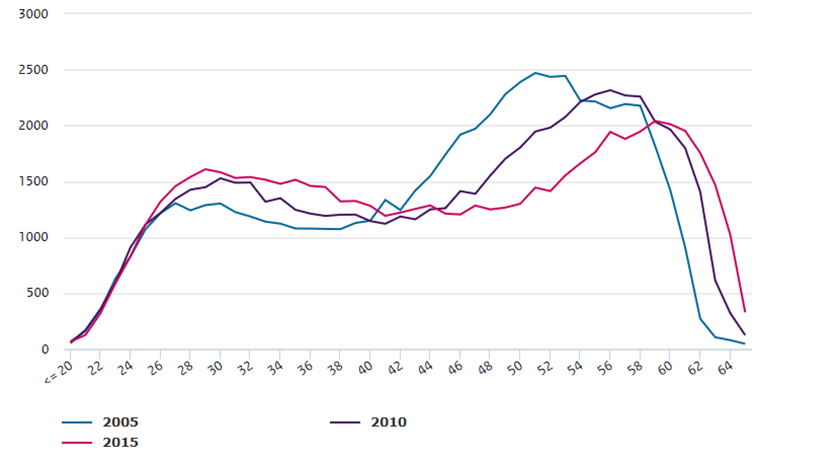

Teacher demographics and other teacher statistics

The Netherlands is facing a demographic decline in its student population. Between 2011 and 2020 the number of students in primary education is expected to decline by 100 000 (a decrease of 7%), with declines of up to 20% in the certain regions. Within these regions, some municipalities face declines of up to 30% of the student population by 2020. The quality of education in smaller schools is harder to ensure, due to financial and staffing problems (Moseley and Owen, 2008; Huitsing and Bosman, 2011). Schools that have experienced a strong demographic decline are more often classified as weak or very weak by the Inspectorate of Education (Haartsen and Wissen, 2012).

Teachers devote a relatively great amount of time to teaching itself (more than 10% above the OESO average). Finding time for other tasks or professional development is a problem. School boards and teacher teams are held accountable for the quality of education. Together, they formulate goals and decide about the roles and responsibilities in achieving these goals.

By law 1200 hours per full-time teacher per year should be devoted to teaching or to teaching tasks (e.g. preparing lessons, checking test results) and 459 hours should be devoted to organizational tasks (e.g. meetings) and professional development. Teachers negotiate with their manager about the distribution of tasks in a school year. The manager tests whether this complies to the criteria of the law and school policy and divides the tasks among teachers. If the majority of teachers approve of this division, it is accepted.

Source: OECD (2016)

Currently there is a teacher shortage in secondary and vocational education in The Netherlands (more older teachers are leaving the workforce compared to the number of entries to the workforce).

In secondary education (SE) the majority of the teachers have permanent, full-time positions.

PE SE SSVE

Permanent 92% 85% 84%

Temporary 8% 15% 16%

Full-time 59% 75% 75%

Part-time 41% 25% 25%

Current trends in educational policy and practice (e.g. relevant curricular reform cycles) & regional differences

The Dutch government has proposed some reforms to boost the equality and quality of education. There are 3 priorities in current Dutch educational policy: (1) find and employ skilled teachers (2) tailor education in line with the student’s personal ability and interests (3) the programmes and activities for both weak and excellent students (4 ) introduce tenders for innovative projects (Veugelers, 2004).

Brief listing of some major historical reforms:

- 1917 Constitution–private (denomination) schools and public schools get equal governmental funding.

- Bologna Declaration 1999–a three-cycle higher-education system consisting of the degrees of bachelor, master and doctor was adopted.

- 1 January 2007 Socrates — promotes knowledge exchange, cooperation and mobility between EU education and training systems.

- 1 August 2007 amendment–under-18s who have finished their period of compulsory education have to continue their schooling to obtain a basic qualification.

- Teachers’ Programme 2013- 2020 (Lerarenagenda 2013-2020)– to develop teachers’ quality

- The Investing in Young People Act (2009-12)– required municipalities to provide work or learning opportunities to 18-27 year-olds, and a salary or allowance in exchange for their work or to support their education.

- The Language and Numeracy Act (2010) –make statements about knowledge and abilities that students must attain in literacy and mathematics at both primary and secondary (general and vocational) levels.

- The Quality in Diversity in Higher Education Act (Wet Kwaliteit in verscheidenheid hoger onderwijs, 2013) – shift the deadline to enter higher education to an early date (May 1st) and set study checks to help students make decisions about their future education.

- The 2014/15 legislation – compulsory student assessment at the end of primary education

- 1 January 2021 New Schools Act – school more closely matches the wishes of parents and pupils.

Current international examinations (PISA, TIMSS)

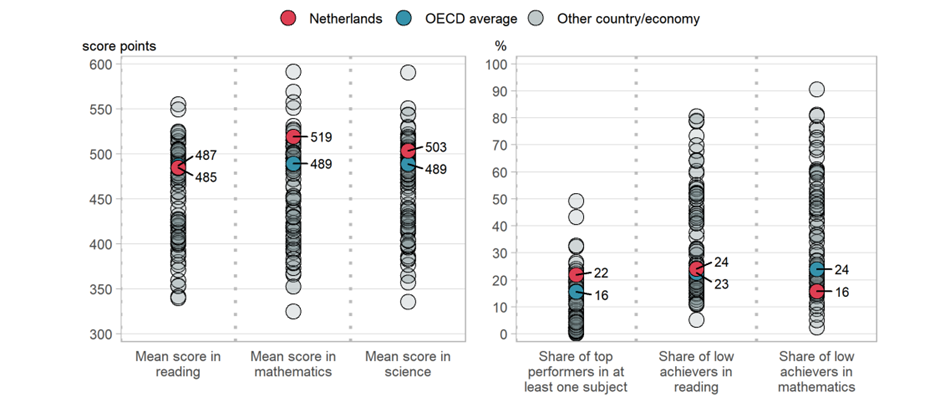

The performance of the Dutch students is amongst the highest in the world. But there has been a decline in performance since PISA 2003. The latest PISA test was conducted in 2018. As the figure shows, reading scores in the Netherlands were not statistically different from the OECD average, mathematics scores were higher than the OECD average, and science scores were higher than the OECD average. In comparison to the OECD average, a higher proportion of Dutch students earned the highest levels of proficiency (Level 5 or 6) in at least one topic, but a lower proportion attained a minimum level of proficiency (Level 2 or higher) in at least one subject.

Source: OECD (2019)

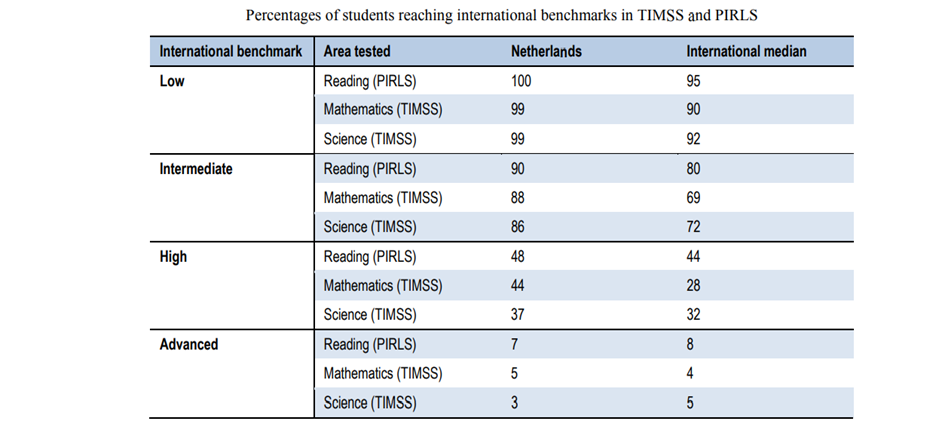

The table shows that Dutch students show overall strong performance in reading, mathematics and science in international tests (PIRLS and TIMSS 2012).

Source: OECD (2014)